This is the final paper presented by Giovanna Patruno, a recent graduate of the Global Digital Marketing and Localization Certification (GDMLC) program. This paper presents the work being produced by students of The Localization Institute’s Global Digital Marketing and Localization Certificate program. The contents of this Paper are presented to create discussion in the global marketing industry on this topic; the contents of this paper are not to be considered an adopted standard of any kind. This does not represent the official position of Brand2Global Conference, The Localization Institute, or the author’s organization.

Target Canada closed its last stores in April 2015, less than two years after launching. Geographic proximity, language and cultural similarities, and market familiarity with the Target brand—the stage was set for a successful expansion. So why did Target fail? Among the most commonly cited factors are an ambitious launch schedule, rapid growth, and inadequate logistics. But a common thread exists: the company failed to align its localization strategy with its global strategy. Target’s inability to understand the Canadian market, to adapt to locale-specific requirements, and to meet consumer expectations ultimately contributed to the demise of Target Canada. Moreover, its failure to provide customers with a local online shopping experience may see Target’s new e-commerce store also fail in Canada.

Researching the Market

Canada is an obvious first choice for U.S. companies starting to expand globally: it has a low barrier to entry and is relatively low in cultural and institutional distance. But despite similarities between the two countries, Canada is not an extension of the U.S. There are some inherent differences, which Target overlooked at the outset.

For one thing, Canada is more culturally and linguistically diverse. It has two official languages, English and French, although Quebec recognizes only French (as such, the Quebec Charter of French Language mandates that products and packaging be available in French). Second, the Canadian market is small, spread over a territory larger than the U.S. but with only 10% of its population, making transportation, distribution, and logistics complicated. Furthermore, differences in Canadian legislations and regulations (such as packaging laws and food tariffs) meant that Target would not be able to serve the Canadian stores from its American distribution network. Finally, locale-specific formats (such as the Canadian dollar, French language characters, and metric measurements) required the company to internationalize its technical infrastructure. But rather than extending support to its existing American supply chain management system, Target opted to deploy a new, unrelated one for Canada, which was far from ready for launch.

Target entered Canada without much thought about the operations and distribution channels. This oversight would consequently have an impact on the supply chain, on product selection, on pricing, and on customer perception.

Exporting the Target Brand

According to Vishwanath and Rigby, successful global expansion hinges on finding the right balance between standardization and localization: “Too much localization can corrupt the brand and lead to ballooning costs. Too much standardization can bring stagnation, dooming a company to dwindling market share and shrinking profit.” This statement rings true for Target.

Known for its clean stores, excellent customer service, great prices, and exclusive product collaborations, Target is ubiquitous in the U.S. But exporting its brand of cheap chic proved to be a challenge: Target had to translate its successful U.S. brand and concept to the Canadian market, while differentiating itself from the already crowded discount landscape. It also had to find the right balance between adapting to the shopping habits of Canadians and delivering what consumers were expecting from Target—the same shopping experience available to them in the U.S. stores.

Target, however, never found that balance nor delivered that shopping experience: empty shelves, limited product offerings, and high prices left Canadian shoppers feeling short- changed. Most importantly, Target lost credibility with Canadian consumers and never recovered from it. As Brian Cornell, CEO of Target, explained in the corporate blog, “[…] we delivered an experience that didn’t meet our guests’ expectations, or our own. Unfortunately, the negative guest sentiment became too much to overcome.”

Understanding consumer shopping habits

By the time Target opened its first stores in March 2013, retail e-commerce sales in Canada were approximately $18.9B CAD, indicating a vast potential online market. Yet, Target chose to focus its expansion on growing its physical stores, not e-commerce, at a time when Canadians had long adopted smartphones, social media, and online shopping.

Canada, in fact, has seen a significant shift in the use the Internet for consumer transactions: consumers can shop any time and from any place, have more choice in the way of price and product selection, and find items not available locally. Needless to say, this is influencing—and changing—shopping behaviors online and offline. For example, cost conscious Canadians like to research a purchase online before buying from a bricks and mortar store, and as many as 61% cite the ability to view in-store inventory online as important or critical. In the case of Target, the retailer had a Canadian website but didn’t sell anything on it; the lack of online presence drove shoppers to the American website to compare Canadian prices and offerings against Target’s American stores, further distancing consumers from the brand.

Although Canadian shoppers have embraced e-commerce, they still like to shop in stores. Adapting to this behavior would require a twofold strategy that combines the e-commerce experience with the in-store experience to create a seamless shopping experience. In other words, implement an omnichannel approach that engages customers online, and, ultimately, drives traffic back to the stores. According to Darrell Rigby, “For omnichannel retailers, websites and mobile apps are not just e-commerce ordering vehicles, they are front doors to the stores. Stores are not just showrooms, they are digitally-enabled inspiration sites, testing labs, purchase points, instantaneous pickup places, help desks, shipping centers, and return locations.” An online store could have at least helped Target collect data to inform decisions on local preferences and demand.

Targeting Canada, again

In September 2015, five months after closing its last Canadian stores, Target launched an e-commerce site to serve the local market. Will it fare better with Canadians the second time around, particularly with only an online presence? In a survey, 65% of Canadian online shoppers cite the ability to return online purchases to a nearby store as important or critical to their purchase decision. Also, Canadians are shopping increasingly at Canadian websites (as opposed to U.S. or foreign websites) because they are starting to find what they want domestically.

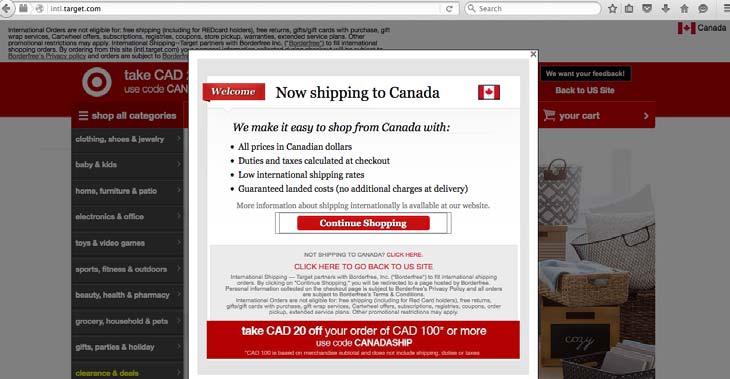

And with Canadians so disappointed with the in-store experience at Target, what is the online experience like? When shoppers visit www.target.ca (ccTLD) they are redirected to www.intl.target.com (subdomain), an international version of its e-commerce site (visiting www.target.com takes Canadian customers to the U.S. site, indicating that geolocation is not enabled). The site does not have a global gateway page.

The site is neither localized nor translated. An English language Welcome message greets Canadian shoppers (Figure below), claiming to “make it easy to shop from Canada.” Users cannot select a different language, making it anything but “easy” for French-speaking customers to shop. Because the company is established outside of Quebec, it is not violating the province’s language laws; however, localizing the site would better accommodate Canada’s Francophone population and make the site more usable to non- English speakers. Moreover, adding more localized content would improve the customer experience, which would lead to a greater likelihood of purchase.

The landing page uses flags to indicate a country site, a practice best avoided because flags “are more political than cultural;” this is particularly true in Quebec, where language and political a tensions run deep. The site also lacks local, dedicated social media channels, once again indicating a lost opportunity to engage with Canadian customers. Clicking the flag enables users to specify (in English) only their country and currency preference. In this case, Canada and US Dollar are selected by default (Figure below).

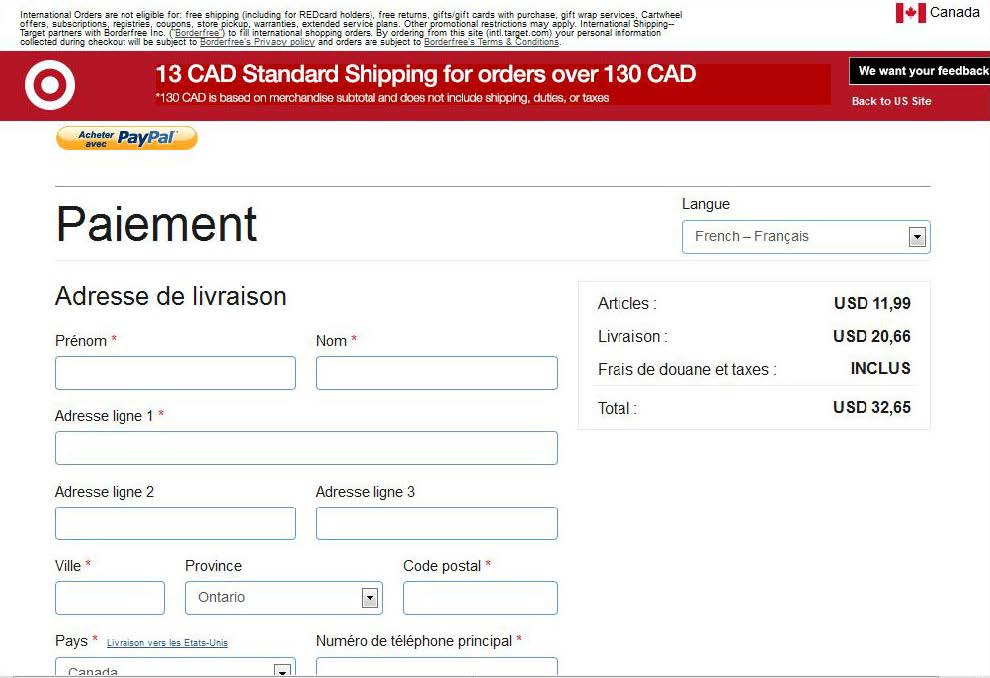

Details on product availability are nonexistent: most products appear to be available to Canadians, but in some cases a product cannot be added to the cart, with no explanation as to why. Enabling customers to shop in U.S. dollars reduces the price differential. To calculate shipping and duties, an item in the amount of $11.99 USD was added to the cart. At checkout, the cost of shipping was $20.66 USD (almost double the cost of the actual item); duties and taxes were included. There is a standard shipping rate of $13 CAD on orders over $130 CAD. The high shipping costs and minimum order charges may be a pain point for Canadians, who may shop around for the best price.20 International orders and product returns are managed by Borderfree; it is not immediately clear how customer service is handled, from where, or by whom.

As for language, customers can select the language of preference only once they get to the checkout page. The checkout form itself is localized, but the rest of the page remains in English (notice, for example, the untranslated banner in Figure below).

Final words

Expect more, pay less. This is Target’s tagline and promise to customers. This is also what Canadians were expecting from Target’s highly anticipated expansion northward: they would finally be able to enjoy the product selection, prices, and in-store experience Target was known for, without having to cross the border into the U.S. Instead, Canadians got empty shelves, poor product selection, and high prices.

Target underestimated its global readiness and overestimated its ability to internationalize. It failed to understand the technical, cultural, and logistical requirements for expansion. Most importantly, Target also missed several opportunities to understand the Canadian market, meet customer expectations, and engage with their local audience. As a result, Canadians never fully accepted the American chain.

With its new “international” e-commerce site, Target is repeating the same mistakes. Canadian shoppers may now have the product selection they wanted from Target, but they now have to absorb high shipping costs and face inconvenient returns due to a lack of stores. Target has also failed to localize and translate their site for the French-speaking communities in Canada; it has continued to miss opportunities to get to know their customers; and it has again failed to deliver on its promise to Canadians to “expect more, pay less.” Today, one question remains worth asking: Did Canada even need Target?

Notes:

Nitish Singh, Localization Strategies for Global E-Business, p. 40.

www.nytimes.com/2014/02/25/business/international/target-struggles-to-compete-in-canada.html

www.canadianbusiness.com/the-last-days-of-target-canada/

https://hbr.org/2006/04/localization-the-revolution-in-consumer-markets

https://hbr.org/2015/01/why-targets-canadian-expansion-failed

www.pymnts.com/in-depth/2015/targets-canadian-omnichannel-fail/

https://corporate.target.com/article/2015/01/qa-brian-cornell-target-exits-canada

www.internetretailer.com/2015/09/01/canada-gets-serious-about-e-commerce

www.digitalclaritygroup.com/target-learns-about-cross-border-commerce-the-hard-way-by-failing-big-in-canada/

www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/oca-bc.nsf/eng/ca02096.html

http://blogs.forrester.com/peter_sheldon/13-04-29-the_state_of_canadian_online_retail_2013

www.digitalclaritygroup.com/target-learns-about-cross-border-commerce-the-hard-way-by-failing-big-in-canada/

https://hbr.org/2014/08/e-commerce-is-not-eating-retail/

https://hbr.org/2006/04/localization-the-revolution-in-consumer-markets

http://blogs.forrester.com/peter_sheldon/13-04-29-the_state_of_canadian_online_retail_2013

www.internetretailer.com/2015/09/01/canada-gets-serious-about-e-commerce

John Yunker, Beyond Borders, p. 183.

http://blogs.forrester.com/peter_sheldon/13-04-29-the_state_of_canadian_online_retail_2013

References

Austen, Ian. “Target Push Into Canada Stumbles.” The New York Times. Web. 25 February 2014. [Accessed February 11, 2016]

Castaldo, Joe. “The Last Days of Target.” Canadian Business. Web. n.d. [Accessed February 6, 2016.]

Dahlhoff, Denise. “Why Target’s Canadian Expansion Failed.” Harvard Business Review. Web. January 2015. [Accessed February 6, 2016.]

Enright, Allison. “Canada gets serious about ecommerce.” Internet Retailer. Web. 1 September 2015. Web. [Accessed February 11, 2016.]

Gibson, Jill Finger. “Target learns about cross-border commerce the hard way by failing big in Canada.” Digital Clarity Group Blog. 1 February 2015. Web. [Accessed February 6, 2016.]

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. “Consumers and Changing Retail Markets.” 27 January 2012. Web. [Accessed March 16, 2016.]

PYMNTS. “Target’s Canadian Omnichannel Fail.” 19 January 2015. Web. [Accessed March 16, 2016.]

Rigby, Darrell. “E-Commerce Is Not Eating Retail.” Harvard Business Review. Web. August 2014. [Accessed February 22, 2016.]

Shaw, Hollie. “Why Target Corp’s online strategy is missing the mark in Canada.” Financial Post. Web. 5 March 2014. [Accessed February 6, 2016.]

Copyright © 2016 The Localization Institute. All rights reserved. This document and translations of it may be copied and furnished to others, and derivative works that comment on or otherwise explain it or assist in its implementation may be prepared, copied, published, and distributed, in whole or in part, without restriction of any kind, provided that the above copyright notice and this section are included on all such copies and derivative works. However, this document itself may not be modified in any way, including by removing the copyright notice or references to The Localization Institute, without the permission of the copyright owners. This document and the information contained herein is provided on an “AS IS” basis and THE LOCALIZATION INSTITIUTE DISCLAIMS ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO ANY WARRANTY THAT THE USE OF THE INFORMATION HEREIN WILL NOT INFRINGE ANY OWNERSHIP RIGHTS OR ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

Author Bio:

Giovanna Patruno is a translator, technical communicator, and localization specialist. Passionate about languages, world cultures, and all things digital, she now specializes in intercultural and international communication, global content strategy, international customer experience, and digital globalization. Giovanna has over 15 years of experience in delivering multilingual content and software products to the global marketplace.

Learn More:

Certificate & Certification in Global Digital Marketing & Localization: www.certificateindigitalmarketing.com

Brand2Global: Global Marketing Conference: www.brand2global.com